3. Initial Build

About this chapter

In this chapter we'll scaffold up a .NET 10 controller-based API and:

- Test it with REST API client

- Remove redundant boilerplate code

- Add initial packages we'll need to implement our data layer

- Place under Git source control and push to GitHub

Learning outcomes:

- Understand how to scaffold up a .NET controller-based API

- Understand the differences between controller-based and minimal APIs

- Understand how to add packages to our .NET project

- Understand the role of a

.gitignorefile - Understand how to initialize a local Git repo and create a commit

- Understand how to create a remote GitHub repository and push a code to it

- The code for this section can be found here on GitHub

- The complete finished code can be found here on GitHub

Scaffold the API

Open a command prompt and navigate to your working directory. For example, I want to place my API project in the following location: /dev/dotnet/Run2, so I'd type:

cd ~/dev/dotnet/Run2

Then run the following command to scaffold up a simple example of a controller-based API:

dotnet new webapi --use-controllers -n CommandAPI

You should see output similar to the following:

The template "ASP.NET Core Web API" was created successfully.

Processing post-creation actions...

Restoring /home/ljackson/dev/dotnet/Run2/CommandAPI/CommandAPI.csproj:

Restore succeeded.

Here we specified:

webapi: this is just a project template, as the name suggests it creates an API. There are many more project templates to choose from type:dotnet new listfor the full list.--use-controllers: if we want to use controllers in our API project we need to explicitly state we want to use them. If not specified the default is used which is the Minimal API pattern.-n CommandAPI: this just specifies the name of our projectCommandAPI

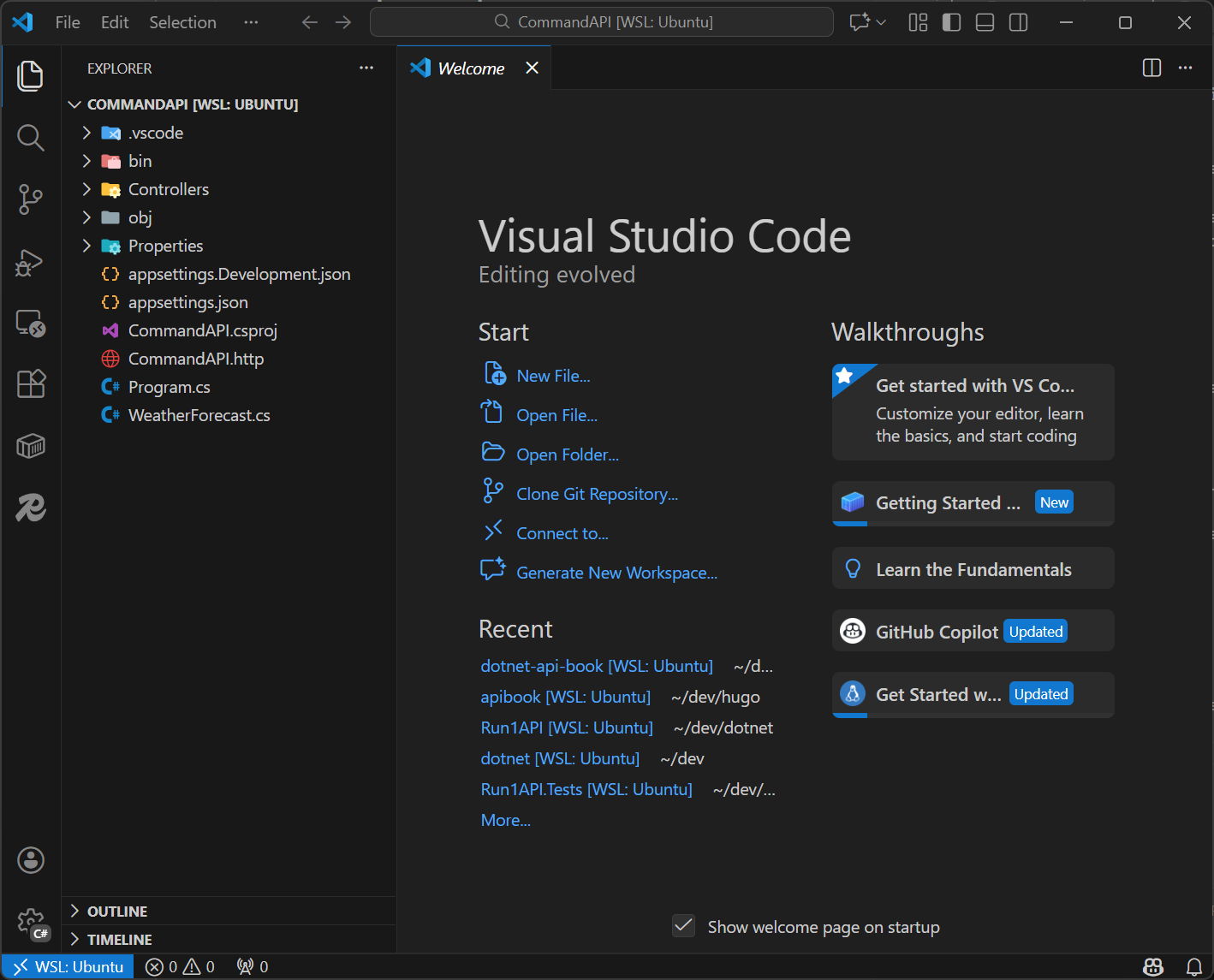

Following a successful creation change into the project directory CommandAPI and start a VS Code session:

cd CommandAPI

code .

This should open a new session of VS Code with our project:

There are 2 concepts I think are worth focusing on briefly here:

- Controller based APIs

- Minimal APIs

You can deep dive these concepts in the relevant theory sections, but I want to cover them quickly here.

These are 2 different design patterns for the internal app structure and have nothing to do directly with the REST API design pattern. Or to put it another way, both Controller and Minimal APIs implement the REST pattern. The differences simply come down to the way we internally choose to architect our API App.

The use of Controllers directly aligns to the MVC pattern (read more about that here), meaning that we implement a controller for each resource-type, in our case that would be:

- PlatformsController

- CommandsController

You could implement the exact same functionality with a minimal API, they just don't employ the organizational mechanism of a controller, the endpoints just directly appear in Program.cs.

I have chosen to use controllers as we will end up with a sufficient number of endpoints by the end of the project build, so I simply want to organize them in a way that makes sense to me. Controllers fit that brief.

Project Tour

Let's take a quick look at some of the main aspects of our project.

bin

The bin folder Contains the final build output (compiled binaries). These are executable files that we can run and distribute. When we come to putting our project under source control using Git, this folder will be excluded as it does not contain source code.

Controllers

This folder will contain all the controllers that we'll create. Currently this contains the WeatherForecastController that has 1 GET action (to return weather data). After testing this in the next section we'll delete this file.

obj

obj Contains intermediate compilation artifacts and temporary files used during the build process. This includes partially compiled code, resolved dependencies, and metadata files that help with incremental builds. Again this folder will be excluded from source control.

Properties

Contains launchSettings.json which allows us to configure how we want the API to start, e.g. what ports we want to assign to both HTTP and HTTPS endpoints.

appsettings

appsettings.json contains any production configuration that we want our application to inherit, and forms part of the overall .NET Configuration Layer. appsettings.Development.json contains any development specific config and will be applied "over" appsettings.json in development environments.

You can read more about the different configuration sources in .NET and their order of precedence here.

CommandAPI.csproj

This is the main project file for our app, let's take a look:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Web">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>net10.0</TargetFramework>

<Nullable>enable</Nullable>

<ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.AspNetCore.OpenApi" Version="10.0.0" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

Here you can see some project config such as:

TargetFramework: in our case this is .NET 10Nullable: do we want to be warned about potential null references. This is useful, but really annoying!ImplicitUsings: this is a feature that if enabled includes common namespaces (aka packages) so we don't need to explicitly include them at the start of each source file. This just reduces the bloat and enhances readability.

You will also see that this is where any additional packages references are added to provide additional functionality in our app. We'll add some new ones in just a bit.

CommandAPI.http

This is HTTP Request file that is used in conjunction with the REST Client VS Code extension we installed earlier. We'll use this to test the scaffolded code.

Program.cs

This is the main entrypoint for our app, and does 2 main things:

-

Sets up services: Creates the web application builder and registers services like controllers and OpenAPI. We'll be working a lot with services and dependency injection as we move through the build so we'll circle back here frequently.

-

Configure the HTTP request pipeline. This is another core concept with .NET APIs relating to a middleware layer that all HTTP requests must traverse. Middleware components can be added and removed, and the order in which they are added is absolutely critical to the correct operation of the app. We'll cover these concepts more as we move through the build, or you can read about them here in the theory section.

WeatherForecast.cs

This is just a simple class that represents a WeatherForecast object, a series of these are passed back from the WeatherForecastController.

Test the API

While we won't be using any of the weather forecast features of the scaffolded app, we can use them to test that everything is working correctly before we proceed to our build. I.e. if this app doesn't work then there is something wrong with our set up that we'll want to remediate before we start adding code.

Organize requests

As we'll be using the HTTP Client extension, along with .http files to test our API throughout the build, let's create a dedicated folder for these artifacts to keep them organized. In the root of the project create a folder called: Requests and move the CommandAPI.http file in there, (you can simply drag and drop this file using the VS Code file explorer).

Update launchSettings.json

Taking a quick look at launchSettings.json you will see that we have 2 profiles (http and https):

{

"$schema": "https://json.schemastore.org/launchsettings.json",

"profiles": {

"http": {

"commandName": "Project",

"dotnetRunMessages": true,

"launchBrowser": false,

"applicationUrl": "http://localhost:5181",

"environmentVariables": {

"ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT": "Development"

}

},

"https": {

"commandName": "Project",

"dotnetRunMessages": true,

"launchBrowser": false,

"applicationUrl": "https://localhost:7276;http://localhost:5181",

"environmentVariables": {

"ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT": "Development"

}

}

}

}

We only want to work with the https profile (which provides both http and https endpoints), so lets remove the http profile.

launchSettings.json should now look like this:

{

"$schema": "https://json.schemastore.org/launchsettings.json",

"profiles": {

"https": {

"commandName": "Project",

"dotnetRunMessages": true,

"launchBrowser": false,

"applicationUrl": "https://localhost:7276;http://localhost:5181",

"environmentVariables": {

"ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT": "Development"

}

}

}

}

NOTE: The port numbers that you'll have will probably be different to the ones I have - that's fine. You can either leave yours as-is (just remember to use your port numbers), or you can update so that they match mine.

Local development certificate

As we have opted to use the https profile, as well as the fact that Program.cs contains the following middleware configuration:

// Configure the HTTP request pipeline.

if (app.Environment.IsDevelopment())

{

app.MapOpenApi();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection(); 👈

app.UseAuthorization();

This middleware will redirect any http requests going to: http://localhost:5181 to the https endpoint (https://localhost:7276), therefore if we do not have a valid https certificate we'll run in to issues.

Generating one is simple:

- Open the integrated terminal in VS Code

CTRL + `(that's Control1 plus the "backtick" symbol - on a US Keyboard that's the key usually abovetab) - Type the following:

dotnet dev-certs https --trust

This should generate a new development certificate for you (or message you to let you know one already existed).

Run and test

Let's run our API, by typing the following at a terminal where you are in the root of the project:

dotnet run

This should render something similar to the following:

➜ CommandAPI dotnet run

Using launch settings from /home/ljackson/dev/dotnet/Run2/CommandAPI/Properties/launchSettings.json...

Building...

warn: Microsoft.AspNetCore.Server.Kestrel.Core.KestrelServer[9]

The ASP.NET Core developer certificate is only trusted by some clients. For information about trusting the ASP.NET Core developer certificate, see https://aka.ms/aspnet/https-trust-dev-cert

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[14]

Now listening on: https://localhost:7276

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[14]

Now listening on: http://localhost:5181

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Application started. Press Ctrl+C to shut down.

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Hosting environment: Development

info: Microsoft.Hosting.Lifetime[0]

Content root path: /home/ljackson/dev/dotnet/Run2/CommandAPI

You'll notice that we still get a warning stating that some clients may not like the local development certificate - if that arises we'll handle that on a case by case basis.

You can see that the app has started and that we can send traffic to 2 endpoints:

http://localhost:5181(although this will be redirected to...)https://localhost:7276

Now open the CommandAPI.http file you placed in to the Requests folder and update it so that we send traffic to the https endpoint, it should look as follows:

@CommandAPI_HostAddress = https://localhost:7276

GET {{CommandAPI_HostAddress}}/weatherforecast/

Accept: application/json

###

Right click on the GET request and select Send Request:

This should open a response window in VS Code and present the results to us:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: close

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Date: Sun, 28 Dec 2025 14:56:47 GMT

Server: Kestrel

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

[

{

"date": "2025-12-29",

"temperatureC": 53,

"temperatureF": 127,

"summary": "Bracing"

},

{

"date": "2025-12-30",

"temperatureC": 11,

"temperatureF": 51,

"summary": "Hot"

},

{

"date": "2025-12-31",

"temperatureC": 31,

"temperatureF": 87,

"summary": "Cool"

},

{

"date": "2026-01-01",

"temperatureC": 6,

"temperatureF": 42,

"summary": "Balmy"

},

{

"date": "2026-01-02",

"temperatureC": 28,

"temperatureF": 82,

"summary": "Cool"

}

]

Given the HTTP/1.1 200 OK response and the fact we have weather data returned this all looks good!

Remove boilerplate

Stop the API from running by issuing a CTRL + C.

We're now going to remove code that we are not going to be using going forward.

- In the

Controllersfolder, delete theWeatherForecastController.csfile. - In the

Requestsfolder, delete theCommandAPI.httpfile. - In the root of the project, delete the

WeatherForecast.csfile.

It goes without saying that our API now doesn't really do anything - don't worry we'll be fixing that soon!

Add packages

We'll be adding quite a lot of packages as we move through the build, but we'll just add the ones we need as and when required. To get started lets add the packages we'll need to support the use of EF Core and PostgreSQL.

At a command prompt in the root of your project2, type the following:

dotnet add package Npgsql.EntityFrameworkCore.PostgreSQL

dotnet add package Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Design

Open the CommandAPI.csproj file to make sure they are there:

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.AspNetCore.OpenApi" Version="10.0.0" />

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Design" Version="10.0.1">

<IncludeAssets>runtime; build; native; contentfiles; analyzers; buildtransitive</IncludeAssets>

<PrivateAssets>all</PrivateAssets>

</PackageReference>

<PackageReference Include="Npgsql.EntityFrameworkCore.PostgreSQL" Version="10.0.0" />

</ItemGroup>

Git

Next we're going to put our project under local source control using Git, so the first thing we want to do is create a .gitignore file. This file tells Git what project artifacts (which may or may not exist) to exclude from source control.

A .gitignore file is exceedingly useful as you only want to add source code to Git, meaning the files that can be used to generate binaries, not the binaries themselves.

It's also used to exclude things like: data files, certain types of config and of course anything secret. You would not want to commit passwords and API keys to Git repo, and certainly not to a public repo that you find on GitHub.

At a command prompt type:

dotnet new .gitignore

This should result in the successful creation of a .gitignore file in the root of the project. The defaults are sufficient for now, if we take a quick look at the # Build results section of the file you'll see:

# Build results

[Dd]ebug/

[Dd]ebugPublic/

[Rr]elease/

[Rr]eleases/

x64/

x86/

[Ww][Ii][Nn]32/

[Aa][Rr][Mm]/

[Aa][Rr][Mm]64/

bld/

[Bb]in/

[Oo]bj/

[Ll]og/

[Ll]ogs/

The highlighted entries ensure that the bin and obj directories and their contents are not committed to Git.

Next we want to put our project under source control, so at a command prompt type:

git init

git add .

git commit -m "Initial commit"

What does this do?

git init: Initializes the local Git repositorygit add .: Adds or stages all files and folders to the repository (excluding those in.gitignore)git commit -m "Initial Commit": This fully "commits" the changes to our repo with a message.

Git is a massive subject, we'll be using it more throughout the book, so I feel that is the best way to learn it rather than discussing it in detail here. If you want to spend some time reading about it you can read the theory section.

If you type:

git branch

This will list the current name of the first branch, in my case this was master. To follow more up to date naming conventions I want to rename this to main, to do so, type:

git branch -M main

You can issue the git branch command again to check that it was renamed.

GitHub

We now want to push our code up to GitHub, so ensure before you move on that:

- You have created an account on GitHub

- You have installed the GitHub CLI

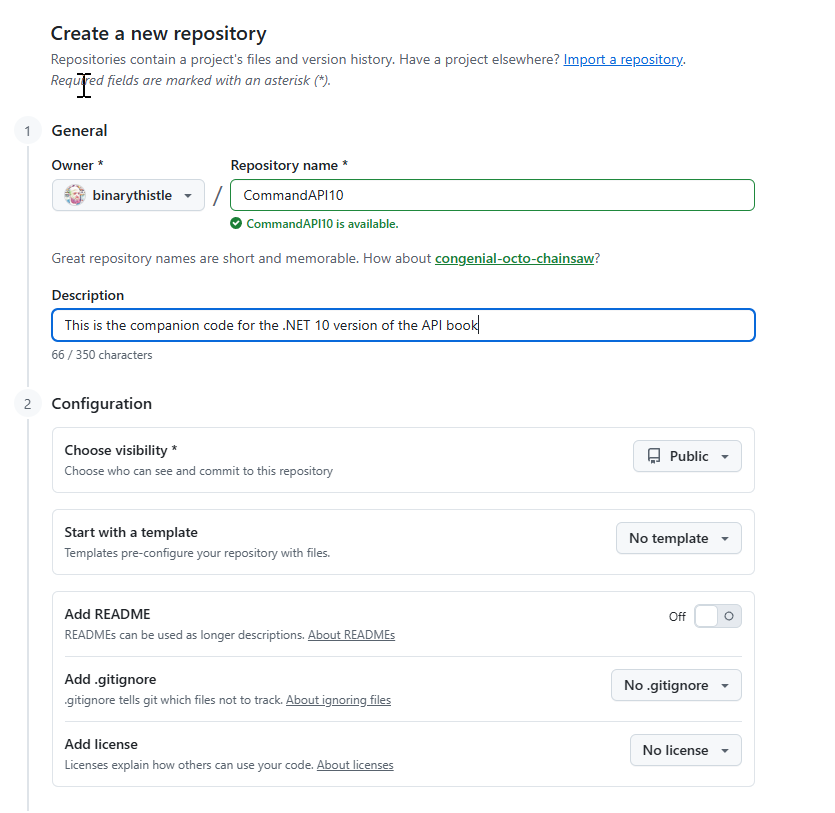

Create repository

Login to GitHub:

- Navigate to

Repositories& click theNewbutton - This will bring up a new repository creation form, I've filled mine out as follows:

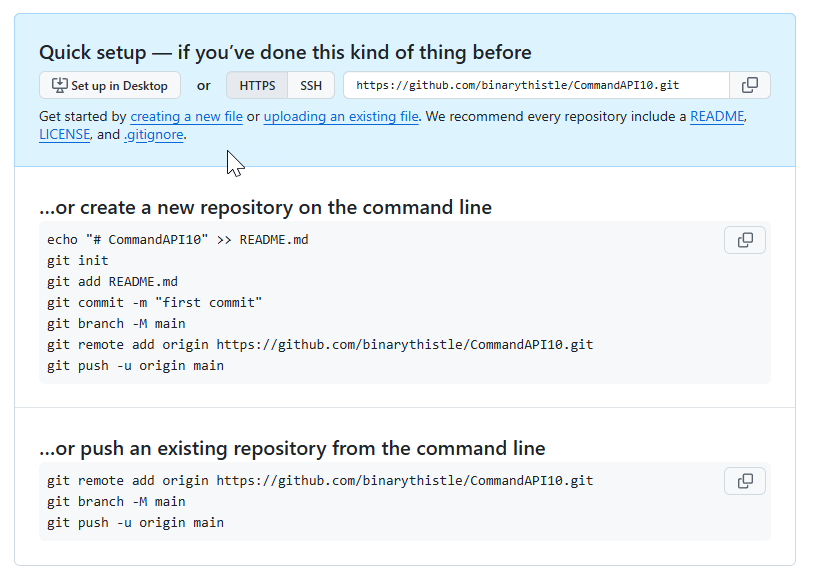

After creating the repo, you'll be presented with something similar to the following:

You should note at this point all we have done is create an empty GitHub repository, it has absolutely no association (yet) with the local Git repository we have created on our machine.

Authenticate to GitHub

Before linking the local repository with our newly created remote GitHub repo, we should ensure that we are authenticated to GitHub from within our CLI, if not then we'd not be able to push our local code to GitHub.

At a command prompt type:

gh auth login

- Select:

GitHub.comfor the account - Select

HTTPSfor the preferred protocol - Select

Login with a web browserfor the authentication method - Copy the code generated at the cli & hit

enter

This will open a browser and continue the authentication flow with GitHub. I'm not going to document that here as it will vary depending on your chosen way to authenticate.

Ultimately you'll be asked to:

- Login to GitHub via the web browser using your chosen auth method

- Provide the cli-generated key when prompted by GitHub

At the end of the flow you should be authenticated to GitHub at the CLI, allowing you to push your code. To do so type the type the following at the prompt:

git remote add origin https://github.com/binarythistle/CommandAPI10.git

git push -u origin main

After a successful push, refreshing the page on GitHub you should see your code!

Conclusion

We have covered a lot of ground in this chapter, and the subject areas were wide ranging - moving forward we'll be a little more focused!

Next up we'll build out the basic data layer that will serve us moving forward.