1. Project Overview

About this chapter

In this chapter we detail the project we're going to build from the following perspectives:

- Value proposition

- Domain model

- Functional

- Technical Component

- Architectural

Learning outcomes:

Just one: a comprehensive understanding of what we are building.

Companion video

📽️ Click to watch the companion video for this section 📽️

Value proposition

As a developer we rely upon a myriad of technologies to undertake our role (it seems like too many sometimes) with new ones emerging all the time.

In the vast majority of cases these tools require some form of command line interaction, more often a significant amount. The cognitive load in trying to remember these commands, even frequently used ones, can be significant.

Enter our API....

This API will act as a repository for all our systems (in our domain we'll call these Platforms), and the Commands associated with them. This means we can connect any client to our API, thus providing command search and retrieval functionality.

Domain Model

Our domain model is exceedingly simple, comprised of 2 primary entities:

- Platform: represents the platforms that can have commands

- A platform can have 0 or more commands

- Command: represents the commands associated to a platform

- A command must have only 1 platform (a command cannot exist without an associated platform)

We will model other entities in our domain, but these are more to support the operational side of the API (e.g. API Key registrations). Here I just wanted to cover the functional domain elements.

We will of course cover all entities in the relevant sections.

Functions of our API

The API will provide the following functionality for both Platforms and Commands (Create, Read, Update and Delete)1 as well as some other operational functions relating to health and authentication:

| Function | HTTP Verb | Route Fragment |

|---|---|---|

| Get all commands (paginated) | GET | /api/commands |

| Get command by ID | GET | /api/commands/{id} |

| Create command | POST | /api/commands |

| Fully update a command | PUT | /api/commands/{id} |

| Partially update a command | PATCH | /api/commands/{id} |

| Delete command | DELETE | /api/commands/{id} |

| Get overall health status | GET | /api/health |

| Get readiness status | GET | /api/health/ready |

| Get PostgreSQL health | GET | /api/health/db |

| Get Redis health | GET | /api/health/cache |

| Get Hangfire health | GET | /api/health/jobs |

| Get all platforms (paginated) | GET | /api/platforms |

| Get platform by ID | GET | /api/platforms/{id} |

| Create platform | POST | /api/platforms |

| Update platform | PUT | /api/platforms/{id} |

| Delete platform | DELETE | /api/platforms/{id} |

| Get commands for platform | GET | /api/platforms/{platformId}/commands |

| Bulk import platforms | POST | /api/platforms/bulk |

| Get bulk import status | GET | /api/platforms/bulk/{jobId}/status |

| Register API key | POST | /api/registrations |

A HTTP request requires that you specify a "verb" when making that request. Looking at the verb attached to call can tell you a lot about the intention on that call. General rule of thumb in the API world is:

GET= read or fetch dataPOST= create dataPUT= update (all) dataPATCH= update (some or all) dataDELETE= destroy data

The verb and route taken together make the endpoint unique. You can read more about these concepts in the REST theory section.

It should be noted that the API we'll build provides much more than just simple CRUD-based endpoints, but we'll discuss those deeper features in the coming chapters.

Technical components

We've already covered the core build technologies (.NET 10 & C#) in the Welcome section, here we'll detail out the other tech we'll be using as part of our build.

PostgreSQL

I've chosen PostgreSQL for our primary database for a number of reasons, including but not limited to:

- It's an awesome production-grade relational db

- It's cross platform

- Related to the above, it's ubiquitous - you will find it everywhere so I feel it's a good DB to use

- There's great .NET support

EF Core

We'll be using EF Core as the projects Object Relational Mapper (ORM) primarily for its feature set, ubiquity and the fact it's by Microsoft. While there are many other fine ORMs out there in the .NET space, EF Core is a solid choice—and as a .NET developer, you will encounter it.

ORMs allow developers to access databases (in this case PostgreSQL) using the native programming language of their given project without the need to write vendor specific SQL. You can read more about ORMs in the theory section.

Redis

The name Redis is synonymous with caching, (even though it can do much more than just act as a cache). In this project however that is what we are using it for.

Fluent Validation

Validations provide a standardized way for developers to define what constitutes a valid input to our system. Validation frameworks come out the box with our .NET API project, (which we'll cover), but moving beyond this we'll opt to use Fluent Validation for defining our system-wide validation rule set. Fluent validation has been picked for its clean separation of concerns (keeping validation logic separate from our Data Transfer Objects), excellent testability, expressive fluent interface that makes validation rules highly readable, and its ability to handle complex validation scenarios.

Mapster

Object mapping provides the ability to easily traverse between object types (in our case this would be Data Transfer Objects and our Domain Models). While this can be achieved manually, as you move to using larger objects with more complex mapping requirement, a mapping framework like Mapster can reduce the burden on the developer.

Serilog

Often overlooked (by me a lot of the time), structured logging is absolutely essential in a production-grade API as it provides a means to track issues that may occur in the platform, thus locating the root cause, and then ultimately implementing a fix. We'll start our structured logging journey by using the ILogger interface by Microsoft, then layer Serilog on top of this to provide rich structured logging with multiple output sinks (console & file).

Auth0

We'll implement a self-rolled API Key authentication solution for one aspect of our look at Authentication, but when we turn our sights to implementing OAuth we'll make use of Auth0 as our authentication provider. I've chosen to use a 3rd party to manage this side of our authentication efforts as it greatly simplifies what we need to build, allowing us to focus on the unique value-proposition of our API. It also backs-off this mission critical component of our API to experts in the domain.

Hangfire

As we move through into the later part of our build we'll implement a batch API endpoint that will process "a lot" of data in an asynchronous way using backend workers. For this feature we'll use Hangfire, principally for its rich feature set, but also for its widespread use in the .NET world.

Other stuff

In the interests of keeping this section somewhat focused, I've only covered the direct technical components that our API will employ, I've not covered the "tech around the sides" of our project like: Docker, Git, GitHub etc. as we'll cover those off in more detail later.

Architecture

I've broken this section down into 3 parts:

- REST: covers API design pattern we'll be using

- MVC: covers internal architectural pattern we'll use for the build

- Solution: Covers the end to end key component structure of the app

This is an outside / in approach to looking at the overall architecture of our API build starting with the exposed interface and working our way inwards.

REST

REST (REpresentational State Transfer) is an architectural style for designing APIs that places the concept of resources (like our Platforms and Commands) front and centre. Resources are identified by URLs and manipulated using HTTP verbs:

| Function | Resource | HTTP Verb | Route Fragment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Get all commands (paginated) | Command | GET | /api/commands |

| Get command by ID | Command | GET | /api/commands/{id} |

| Create command | Command | POST | /api/commands |

| Fully update a command | Command | PUT | /api/commands/{id} |

| Partially update a command | Command | PATCH | /api/commands/{id} |

| Delete command | Command | DELETE | /api/commands/{id} |

| Get all platforms (paginated) | Platform | GET | /api/platforms |

| Get platform by ID | Platform | GET | /api/platforms/{id} |

| Create platform | Platform | POST | /api/platforms |

| Update platform | Platform | PUT | /api/platforms/{id} |

| Delete platform | Platform | DELETE | /api/platforms/{id} |

| Get commands for platform | Command | GET | /api/platforms/{platformId}/commands |

| Bulk import platforms | Platform | POST | /api/platforms/bulk |

| Get bulk import status | Platform | GET | /api/platforms/bulk/{jobId}/status |

This approach promotes stateless communication between client and server, where each request contains all the information needed to process it.

REST is by far and away the most popular API design pattern2 (others include GraphQL, gRPC etc.), and is easy to pick up and learn, hence why we're using it. You can read more about the intricacies of REST in the Theory section.

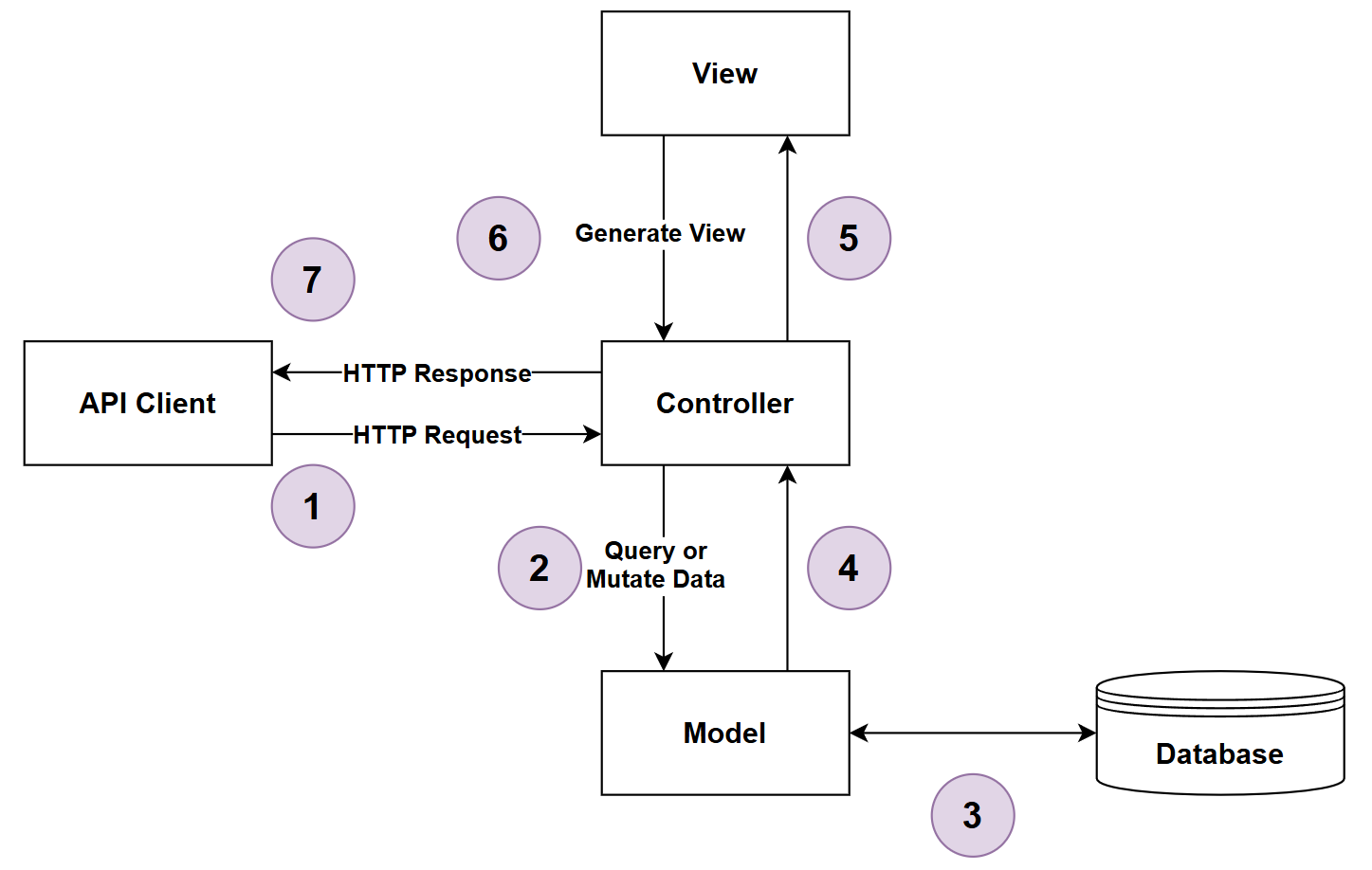

MVC

Moving from the external or client facing architecture of our API, we turn now to the internal architecture of the API and the Model View Controller (MVC) pattern.

Clients using the API would not know, nor should they care about this aspect of our architecture.

MVC (Model View Controller) is an architectural pattern that separates an application into three interconnected components: Models (data and business logic), Views (presentation layer), and Controllers (request handling and flow control). In the context of .NET API development, the pattern is slightly modified—Controllers handle incoming HTTP requests and return data responses, Models represent our domain entities and DTOs, while the "View" layer is effectively the JSON serialization of our response objects rather than HTML templates. This separation of concerns promotes cleaner, more maintainable code by ensuring each component has a distinct responsibility.

You can read more on the MVC patter in the Theory section.

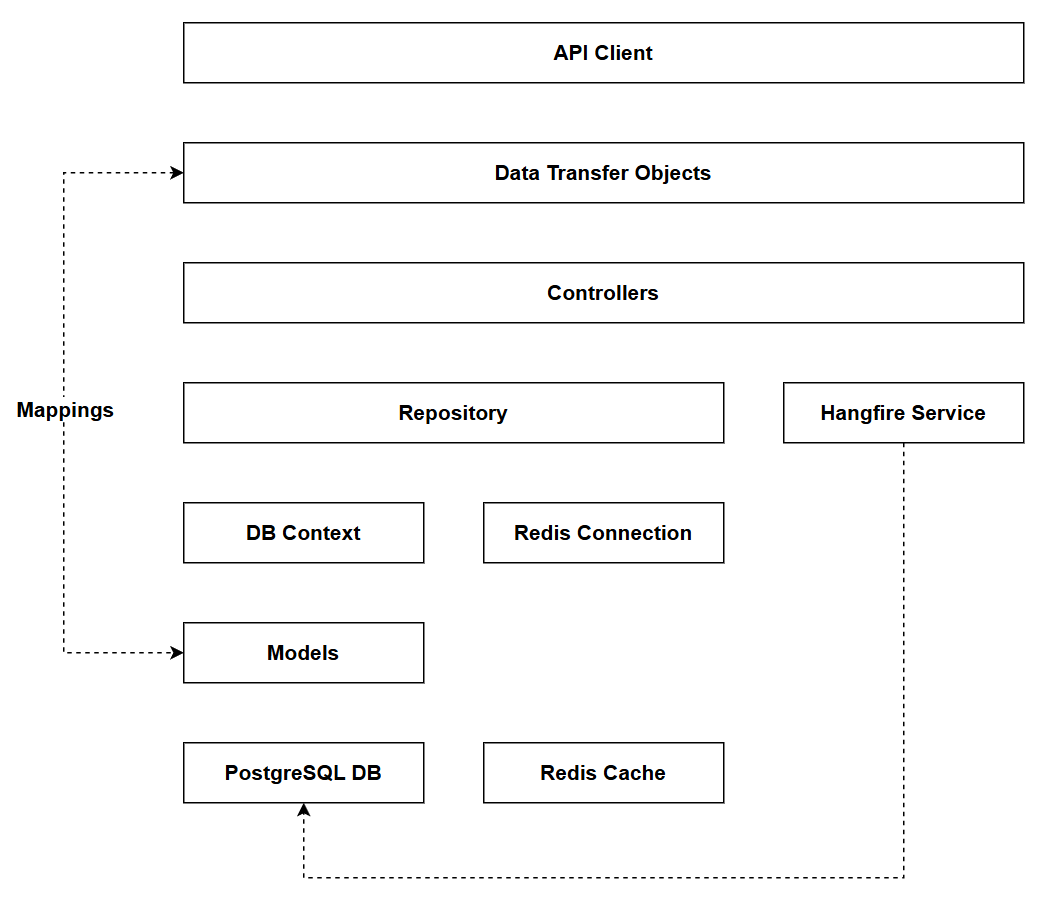

Solution Architecture

Finally we take a look at the overall high-level solution architecture, from top to bottom we have:

- API Client: not technically part of our solution, but we will make use of http request files from within our project to test our endpoints

- Data Transfer Objects (DTOs): these act as the external facing contract with our client.

- We'll use Fluent Validation here to ensure DTOs used for system inputs are valid

- We'll use Mapster to provide mappings between DTOs and the Domain Models

- Controllers: implemented as part of the MVC pattern, controllers will act as the orchestrators for API requests.

- Hangfire Service: This service will be responsible for managing bulk API requests through the use of background workers.

- Repository: We're going to make use of the Repository Pattern to provide a layer of further abstraction between our database and our app code. A possibly controversial choice we'll cover the reasons for its use in that chapter.

- DB Context: Provided by EF Core, the DB Context "models" the Domain Models down to the PostgreSQL DB and acts as an intermediary between the Repository and the PostgreSQL Database.

- Redis Connection: Used to connect into our Redis Cache (we don't use a DB Context here)

- Models: Internal representations of our domain, exposed externally in this instance as DTOs. Models are ultimately represented down at our PostgreSQL database.

- PostgreSQL DB: The database persistence layer used to store domain as well as operation data.

- Redis Cache: Key Value pair database used in this instance as a supplementary cache to speed up the serving of some data.

We will revisit this architecture throughout the build, using it to aid understanding and mark progress through the build.

Project Structure

The folder structure of our project will be as follows (don't worry if you don't know what some of those folders relate to yet - you will soon!):

APIProject/

├── Controllers/

├── Data/

├── Dtos/

├── Logs/

├── Mappings/

├── Middleware/

├── Migrations/

├── Models/

├── Properties/

├── Requests/

├── Services/

├── Validators/

└── wwwroot/

I have explicitly gone for this technical or layer-based view as this is a technical guide covering these exact concepts, so segmenting them in this way made sense to me (for this book).

It is worth mentioning that you do have another common approach to structuring your project: the Domain or Feature view. This segments the project around domain lines (e.g. Platforms and Commands for example), and may look something like this:

APIProject/

├── Platforms/

│ ├── PlatformsController.cs

│ ├── Platform.cs

│ ├── PlatformCreateDto.cs

│ ├── PlatformReadDto.cs

│ ├── IPlatformRepository.cs

│ ├── PgSqlPlatformRepository.cs

│ └── PlatformValidator.cs

├── Commands/

│ ├── CommandsController.cs

│ ├── Command.cs

│ ├── CommandCreateDto.cs

│ └── ...

└── Registrations/

└── ...

I've decided against this approach for the reasons already stated above, but also because we have a small domain, and as such I think it would make the project less readable.

When implementing your own projects, where the domain is more complex and you understand the technical concepts involved, this approach can be a good one.

Conclusion

That's it for this chapter. Both a lot of information, while at the same time, not deep-diving at all! Bear in mind this chapter is just a high-level overview of what we're about to embark on, so I've tried to keep it as light as possible, while at the same time providing enough grounding on what we'll be building.

Do not worry if at this point you don't understand all the concepts involved, we'll dive into them in much more detail as we progress with the practical build.

Let's start to get our hands dirty, and set up our development environment in the next section!